March 2025

Update to In Her Own Words, dated December 2017. Read 2017’s here.

I recently found something I hadn’t seen in a few years: many volumes of paperwork from all the clinical trials I’ve participated in since diagnosis with stage IV ovarian cancer in 2010. Each time I experienced a relapse, I became involved with a different trial, and wow, there were 4!

The first was the Phase 1 angiogenesis inhibitor testing oral BIBF. I was followed for several years, but because it was a double-blind study, I never learned if I received the study drug or placebo. The second was the Phase 1 vaccine trial at Seattle Cancer Care Alliance, which tested the immune response to the IGFBP target. The third was the single agent Doxil, given at a higher dose than would be given for standard-of-care treatment.

The fourth and the most important trial to me was the Phase 1B at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston, Texas, where I tested Olaparib plus an mTOR inhibitor taken orally twice daily. These drugs had never been taken in combination; only Olaparib had recently received FDA approval, and the Mtor was investigational. The results were surprising; within 7 weeks of starting the trial, my abnormal results, both by serology (labs) and imaging, had normalized. Because I live in Oregon and the trial required constant monitoring for the first 5 weeks, I needed a leave of absence from work, and the team at MD Anderson helped me to find short-term housing nearby. The trial had no finite period described, and there were no side effects or lack of efficacy for me, which would have indicated a reason to cease. I stayed on the protocol for 8 years, and during the entire time, I had no evidence of disease and was termed an “unusual responder”! At the end of 8 years, I decided to stop the trial because there was a small risk of developing a hematologic disorder, and none of the clinicians knew if the extended time would induce a cumulative risk. It has been 2 years since ending the therapy, and at every quarterly check, I still show no evidence of disease.

Needless to say, I am a grateful recipient of novel clinical research by brilliant and dedicated physicians, none of which would be possible without governmental grants and a considerable measure of philanthropy. The current uncertainty regarding policy, as the NIH would cap reimbursement for indirect costs incurred in research, could spell a halt to many areas of development, not just for cancer, but for Alzheimer’s, heart disease, Parkinson’s, and many others. “Indirect costs” include, for example, those needed for building maintenance, funding of technicians and statisticians to do the work, purchase, and care of lab mice, and funding for maintaining records and compliance, etc. Part of my advocacy work will now include writing letters to leaders in government so that the research we patients depend upon will have at least a hopeful chance of continuing.

Tami Ward My surgery went well, and the doctor was able to get clean margins. I was recovering and went in for…

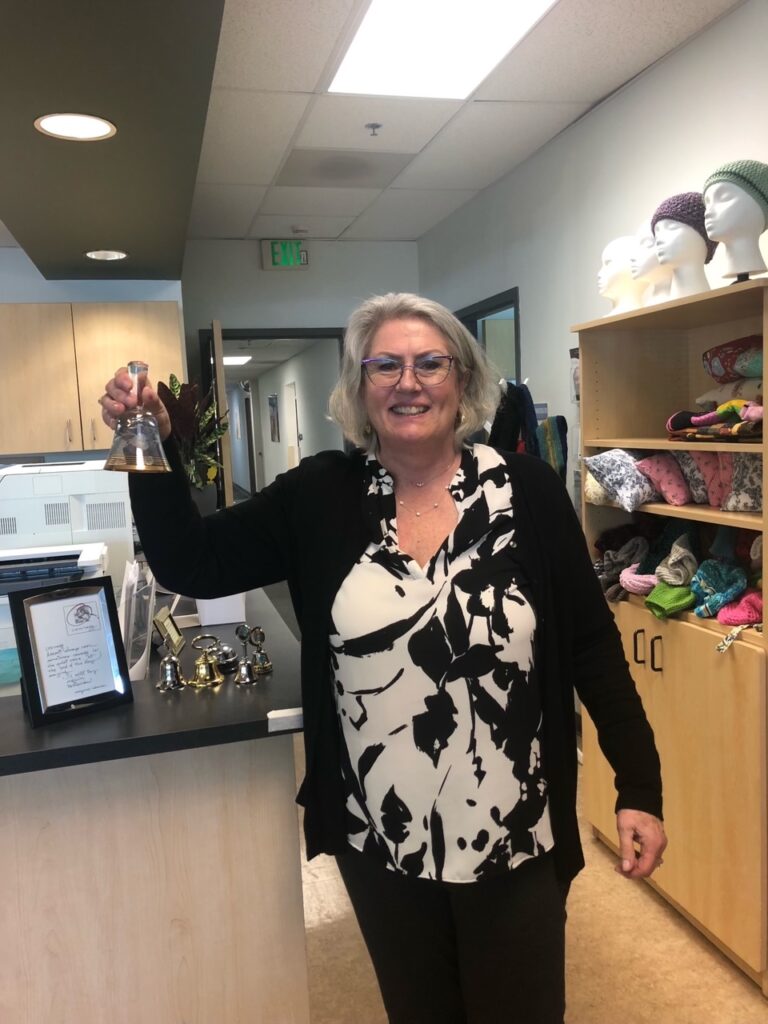

Tami Ward My surgery went well, and the doctor was able to get clean margins. I was recovering and went in for… Diane Sarver Needless to say, I am a grateful recipient of novel clinical research by brilliant and dedicated physicians, none of which would be…

Diane Sarver Needless to say, I am a grateful recipient of novel clinical research by brilliant and dedicated physicians, none of which would be… Candace McKanna Be assertive in finding providers that truly suit you, as your life literally depends on it. In November 2021, I…

Candace McKanna Be assertive in finding providers that truly suit you, as your life literally depends on it. In November 2021, I… Carissa Thompson I continued pushing my provider for more tests. An ultrasound showed a small mass on my left ovary that was…

Carissa Thompson I continued pushing my provider for more tests. An ultrasound showed a small mass on my left ovary that was… Julia Tastor The community I have and the support I have found are really unbelievable. Who thinks they would get cancer at…

Julia Tastor The community I have and the support I have found are really unbelievable. Who thinks they would get cancer at… Amy Kula I think I learned the lesson of speaking up a bit more through the annoyances: calling out doctors for not…

Amy Kula I think I learned the lesson of speaking up a bit more through the annoyances: calling out doctors for not… Sancy Hilgenberg I have a meditation practice that usually reins in my most stubborn negative thoughts and emotions and, at best, leaves…

Sancy Hilgenberg I have a meditation practice that usually reins in my most stubborn negative thoughts and emotions and, at best, leaves… Ann Werner Soon after surgery, I attended a meeting of the Ovarian Cancer Alliance of Oregon and SW Washington. It was a…

Ann Werner Soon after surgery, I attended a meeting of the Ovarian Cancer Alliance of Oregon and SW Washington. It was a… Marion Gust My oncologist said I wouldn’t be here today without the surgery and chemo infusions, so I’m currently living life to…

Marion Gust My oncologist said I wouldn’t be here today without the surgery and chemo infusions, so I’m currently living life to… Nancy Davis Along with my faith, my family keeps me positive, although negative thoughts sometimes creep in. My dearest friends and my…

Nancy Davis Along with my faith, my family keeps me positive, although negative thoughts sometimes creep in. My dearest friends and my… Cheryl Terrusa Throughout this time, though, I experienced depression and sadness and feared a recurrence of cancer. I couldn’t resolve these things,…

Cheryl Terrusa Throughout this time, though, I experienced depression and sadness and feared a recurrence of cancer. I couldn’t resolve these things,… Sayla Hachey It is important to know ovarian cancer symptoms and risk factors. I had symptoms of ovarian cancer. If I had…

Sayla Hachey It is important to know ovarian cancer symptoms and risk factors. I had symptoms of ovarian cancer. If I had… Nikki Wheeler I had my last scan in January, and it showed no sign of recurrence and no change in the lymph…

Nikki Wheeler I had my last scan in January, and it showed no sign of recurrence and no change in the lymph… Manda Buttita I used to express my gratitude that I'd only had cancer once and say I didn't think I could do…

Manda Buttita I used to express my gratitude that I'd only had cancer once and say I didn't think I could do… Jennifer Jones What I have learned and love about the OCAOSW support meetings is that every woman afflicted with this illness is…

Jennifer Jones What I have learned and love about the OCAOSW support meetings is that every woman afflicted with this illness is… Aileah Carlson Over the course of the week, I became close with women of all ages, some newly diagnosed like myself and…

Aileah Carlson Over the course of the week, I became close with women of all ages, some newly diagnosed like myself and… Heather Frazier The fear of a recurrence lives just below the surface while I move forward with my life. I have been…

Heather Frazier The fear of a recurrence lives just below the surface while I move forward with my life. I have been… Ruth Anne Weisbard During the 21 years of follow-up, my CA 125 was always about 2. In 2022, it was 10, but the…

Ruth Anne Weisbard During the 21 years of follow-up, my CA 125 was always about 2. In 2022, it was 10, but the… Camille Oldenburg I would like to focus also on what I learned during the past 2 ½ years. Until my diagnosis at…

Camille Oldenburg I would like to focus also on what I learned during the past 2 ½ years. Until my diagnosis at… Anita Krivitzky Fast forward: It was a long recovery, but I am back pet sitting and very busy with volunteering. I see…

Anita Krivitzky Fast forward: It was a long recovery, but I am back pet sitting and very busy with volunteering. I see… Vicki Brick-Zupancic Survivors have advised me that the cancer journey is a marathon, not a sprint. I know there will be ups…

Vicki Brick-Zupancic Survivors have advised me that the cancer journey is a marathon, not a sprint. I know there will be ups… Missy Fant Listen to your body and advocate for yourselves if your physician isn't available or listening to you.

Missy Fant Listen to your body and advocate for yourselves if your physician isn't available or listening to you. Jen Shubert Finally, in February, I got a call back. My doctor recommended I go to a gynecologist in Idaho to have…

Jen Shubert Finally, in February, I got a call back. My doctor recommended I go to a gynecologist in Idaho to have… Liliana Saunero-Nava To all the women present- PLEASE listen to your bodies, get yearly exams with a pelvic exam, and NEVER let…

Liliana Saunero-Nava To all the women present- PLEASE listen to your bodies, get yearly exams with a pelvic exam, and NEVER let… Rachel Li When my treatment wrapped up, I began to volunteer with the Ovarian Cancer Alliance’s Survivors Teaching Students to help others…

Rachel Li When my treatment wrapped up, I began to volunteer with the Ovarian Cancer Alliance’s Survivors Teaching Students to help others… Ann Thomas My take-a-ways are family and friends. Nurture what you have, stay in touch, and above all don’t hold grudges. They’re…

Ann Thomas My take-a-ways are family and friends. Nurture what you have, stay in touch, and above all don’t hold grudges. They’re… Alice McElhaney I had been experiencing a variety of symptoms for several months, but cancer never crossed my mind. Pain here and…

Alice McElhaney I had been experiencing a variety of symptoms for several months, but cancer never crossed my mind. Pain here and… Tracy Bain Going through cancer treatment is as much a physical as it is a mental battle. It doesn’t matter what type…

Tracy Bain Going through cancer treatment is as much a physical as it is a mental battle. It doesn’t matter what type… Jenna Jenkins My primary care physician insisted I was experiencing indigestion. I could’ve easily left my doctor’s office that day and chalked…

Jenna Jenkins My primary care physician insisted I was experiencing indigestion. I could’ve easily left my doctor’s office that day and chalked… Kathleen Fallon I’ve found that keeping cancer at bay has been like having a regular job with irregular hours. I guess it’s…

Kathleen Fallon I’ve found that keeping cancer at bay has been like having a regular job with irregular hours. I guess it’s… Samantha Caggiano The best information I was given by my gynecologic oncologist was that ovarian cancer is considered a chronic condition. I…

Samantha Caggiano The best information I was given by my gynecologic oncologist was that ovarian cancer is considered a chronic condition. I… Heather Braaten I felt great when I went in to see my primary care physician a month earlier about some lumps in…

Heather Braaten I felt great when I went in to see my primary care physician a month earlier about some lumps in… Louise Smith I had gained some weight and brushed it off as the stress of it all. Then came the changes to…

Louise Smith I had gained some weight and brushed it off as the stress of it all. Then came the changes to… Sherry Hanson Sherry Hanson May 2009 I underwent abdominal surgery, was diagnosed with stage II C epithelial ovarian cancer, and had a…

Sherry Hanson Sherry Hanson May 2009 I underwent abdominal surgery, was diagnosed with stage II C epithelial ovarian cancer, and had a… Anita Krivitzky Anita Krivitzky March 2022 Update to In Her Own Words dated April 2014. Read 2014’s here. I have been very…

Anita Krivitzky Anita Krivitzky March 2022 Update to In Her Own Words dated April 2014. Read 2014’s here. I have been very… Carol Brooks Carol Brooks February 2022 Like most of us, the diagnosis of my ovarian cancer was lengthy and difficult, but I…

Carol Brooks Carol Brooks February 2022 Like most of us, the diagnosis of my ovarian cancer was lengthy and difficult, but I… Ashley Hows Ashley Hows January 2022 In September of 2020, at the age of 27, I was diagnosed with Stage 1A ovarian…

Ashley Hows Ashley Hows January 2022 In September of 2020, at the age of 27, I was diagnosed with Stage 1A ovarian… Dianne Helmer Dianne Helmer December 2021 I am a six year survivor of stage III B ovarian cancer. My cancer is incurable,…

Dianne Helmer Dianne Helmer December 2021 I am a six year survivor of stage III B ovarian cancer. My cancer is incurable,… Sandi Jossi Sandi Jossi November 2021 Mine is a simple story: While working one day in the summer of 2007 I had…

Sandi Jossi Sandi Jossi November 2021 Mine is a simple story: While working one day in the summer of 2007 I had… Diane Morris Diane Morris October 2021 On a Saturday evening I felt a pain in my left side while I was taking…

Diane Morris Diane Morris October 2021 On a Saturday evening I felt a pain in my left side while I was taking… Kristen Lunden Kristen Lunden September 2021 In April 2018 I started experiencing abdominal discomfort and other symptoms which gradually affected my job…

Kristen Lunden Kristen Lunden September 2021 In April 2018 I started experiencing abdominal discomfort and other symptoms which gradually affected my job… Lindsey Spencer, Honolulu Lindsey Spencer, Honolulu August 2021 In May 2014, at the age of 28, I was diagnosed with ovarian cancer. At…

Lindsey Spencer, Honolulu Lindsey Spencer, Honolulu August 2021 In May 2014, at the age of 28, I was diagnosed with ovarian cancer. At… Mary Evans, retired hospice R.N. Mary Evans, retired hospice R.N. July 2021 My ovarian cancer journey has been a long one, nor is it over…

Mary Evans, retired hospice R.N. Mary Evans, retired hospice R.N. July 2021 My ovarian cancer journey has been a long one, nor is it over… Sally Guyer Sally Guyer June 2021 I never know where to start when telling my cancer story, which is indicative of the…

Sally Guyer Sally Guyer June 2021 I never know where to start when telling my cancer story, which is indicative of the… The Dianes The Dianes May 2021 Diane Elizondo and Diane O'Connor met in 2002 in Vancouver, WA after they had both been…

The Dianes The Dianes May 2021 Diane Elizondo and Diane O'Connor met in 2002 in Vancouver, WA after they had both been… Beth Kupper-Herr Beth Kupper-Herr April 2021 Aloha from Hawaii! I might be the luckiest ovarian cancer survivor you'll ever hear about. In…

Beth Kupper-Herr Beth Kupper-Herr April 2021 Aloha from Hawaii! I might be the luckiest ovarian cancer survivor you'll ever hear about. In… Mary Pegg Mary Pegg March 2021 So, my Ovarian Cancer journey, or I should say trip thru h— and back, began in…

Mary Pegg Mary Pegg March 2021 So, my Ovarian Cancer journey, or I should say trip thru h— and back, began in… Susan Gottbreht Susan Gottbreht February 2021 My name is Susan Gottbreht but I go by Sue. My husband took an early retirement…

Susan Gottbreht Susan Gottbreht February 2021 My name is Susan Gottbreht but I go by Sue. My husband took an early retirement… Camille Williams, Honolulu Camille Williams, Honolulu January 2021 It was like any other Tuesday for 16 year old me — After my last…

Camille Williams, Honolulu Camille Williams, Honolulu January 2021 It was like any other Tuesday for 16 year old me — After my last… Vicki Grandy, Portland Vicki Grandy, Portland December 2020 "That is really serious, isn't it?" The news of my Ovarian Cancer diagnosis frequently brings…

Vicki Grandy, Portland Vicki Grandy, Portland December 2020 "That is really serious, isn't it?" The news of my Ovarian Cancer diagnosis frequently brings… Melanie Chu, Portland Melanie Chu, Portland November 2020 Hindsight! I had the classic symptoms of ovarian cancer but was ignorant of the cancer.…

Melanie Chu, Portland Melanie Chu, Portland November 2020 Hindsight! I had the classic symptoms of ovarian cancer but was ignorant of the cancer.… Wendy Clifton Wendy Clifton October 2020 In 2015 I was living in a small town in Northern California. The town, Ukiah, was…

Wendy Clifton Wendy Clifton October 2020 In 2015 I was living in a small town in Northern California. The town, Ukiah, was… Amy Kay Lindh Amy Kay Lindh September 2020 At 48 years old I had my yearly pap smear physical and was told all…

Amy Kay Lindh Amy Kay Lindh September 2020 At 48 years old I had my yearly pap smear physical and was told all… Antra Boyd Antra Boyd August 2020 It was September of 2018 while I was on my computer, working on behalf of a…

Antra Boyd Antra Boyd August 2020 It was September of 2018 while I was on my computer, working on behalf of a… Helaine Gross Helaine Gross July 2020 I live in Portland and am now two years post treatment. I feel good with no…

Helaine Gross Helaine Gross July 2020 I live in Portland and am now two years post treatment. I feel good with no… Noel Rademacher Noel Rademacher May 2020 In 2012 my fairytale was taking place. I was 36, engaged to a wonderful man, and…

Noel Rademacher Noel Rademacher May 2020 In 2012 my fairytale was taking place. I was 36, engaged to a wonderful man, and… Paula McNeill Paula McNeill April 2020 It was Labor Day Weekend, 2002, and I was spending it with family, off the grid,…

Paula McNeill Paula McNeill April 2020 It was Labor Day Weekend, 2002, and I was spending it with family, off the grid,… Terrilyn Chun Terrilyn Chun March 2020 My cancer journey began in July 2017. For several months I had been experiencing symptoms which…

Terrilyn Chun Terrilyn Chun March 2020 My cancer journey began in July 2017. For several months I had been experiencing symptoms which… Carol Hoefer Carol Hoefer February 2020 When I was diagnosed with DCIS breast cancer in 2001, I considered my options for treatment…

Carol Hoefer Carol Hoefer February 2020 When I was diagnosed with DCIS breast cancer in 2001, I considered my options for treatment… Jan Chapman Jan Chapman January 2020 Surprises can be very nice. When the surprise is medical, however – you think that you…

Jan Chapman Jan Chapman January 2020 Surprises can be very nice. When the surprise is medical, however – you think that you… Leona Sandau Leona Sandau December 2019 It all began on Christmas eve 2002… After a few years of constant pain in my…

Leona Sandau Leona Sandau December 2019 It all began on Christmas eve 2002… After a few years of constant pain in my… Margaret Rice Margaret Rice November 2019 My name is Margaret Rice, and I live in Grants Pass, Oregon. It was a normal…

Margaret Rice Margaret Rice November 2019 My name is Margaret Rice, and I live in Grants Pass, Oregon. It was a normal… Paulette Page Paulette Page October 2019 Late January 2010 at age 64, while sharing with my spouse (Rod), daughter, son and partners…

Paulette Page Paulette Page October 2019 Late January 2010 at age 64, while sharing with my spouse (Rod), daughter, son and partners… Kim Rhodes Kim Rhodes August 2019 Hello, my name is Kim Rhodes, and this is my story. Background first: I am not…

Kim Rhodes Kim Rhodes August 2019 Hello, my name is Kim Rhodes, and this is my story. Background first: I am not… Anne Fischer Anne Fischer July 2019 In April of 2010 I was diagnosed with a granulosa cell tumor, which is a slow-growing…

Anne Fischer Anne Fischer July 2019 In April of 2010 I was diagnosed with a granulosa cell tumor, which is a slow-growing… Kay McGuire Kay McGuire June 2019 This is my favorite photo of my granddaughter and me. We were at the "Bring your…

Kay McGuire Kay McGuire June 2019 This is my favorite photo of my granddaughter and me. We were at the "Bring your… Becky Haas Becky Haas May 2019 Like many who have written this column before me, I noticed discomfort in my lower abdomen,…

Becky Haas Becky Haas May 2019 Like many who have written this column before me, I noticed discomfort in my lower abdomen,… Rowena Musser Rowena Musser April 2019 I was working 10-12 hour days in a fairly demanding job and was tired all of…

Rowena Musser Rowena Musser April 2019 I was working 10-12 hour days in a fairly demanding job and was tired all of… Tonya Sarver Tonya Sarver March 2019 My story begins in the fall of 2017. It was an exhausting and stressful time for…

Tonya Sarver Tonya Sarver March 2019 My story begins in the fall of 2017. It was an exhausting and stressful time for… Linda Lynch Linda Lynch February 2019 I remember not feeling well around our anniversary September 20, 1998. We lived in Thousand Oaks,…

Linda Lynch Linda Lynch February 2019 I remember not feeling well around our anniversary September 20, 1998. We lived in Thousand Oaks,… Alex Mendolsohn Alex Mendolsohn January 2019 I had just turned 61 and had returned from a trip to southeast Asia when I…

Alex Mendolsohn Alex Mendolsohn January 2019 I had just turned 61 and had returned from a trip to southeast Asia when I… Joan Meyerhoff Joan Meyerhoff December 2018 My first grandchild, Rosland, was born on October 3rd. Early each morning in the first week…

Joan Meyerhoff Joan Meyerhoff December 2018 My first grandchild, Rosland, was born on October 3rd. Early each morning in the first week… Penny Hummel Penny Hummel November 2018 A year after I joined the ovarian cancer survivor club, I sometimes still blink in disbelief…

Penny Hummel Penny Hummel November 2018 A year after I joined the ovarian cancer survivor club, I sometimes still blink in disbelief… Sandy Moreno Sandy Moreno October 2018 As I was thinking about telling "My Story" what came to my mind first were the…

Sandy Moreno Sandy Moreno October 2018 As I was thinking about telling "My Story" what came to my mind first were the… Barb Swanson Sanders Barb Swanson Sanders August 2018 I have been an educator for 47 years, including a kindergarten teacher, an elementary school…

Barb Swanson Sanders Barb Swanson Sanders August 2018 I have been an educator for 47 years, including a kindergarten teacher, an elementary school… Larissa Ienna Larissa Ienna July 2018 "You can't control how you go." This is what I've been told by countless people since…

Larissa Ienna Larissa Ienna July 2018 "You can't control how you go." This is what I've been told by countless people since… Cheryl Terrusa Cheryl Terrusa June 2018 Cheryl Terrusa In Her Own Words June 2018 I've never felt I was lucky. My grandparents…

Cheryl Terrusa Cheryl Terrusa June 2018 Cheryl Terrusa In Her Own Words June 2018 I've never felt I was lucky. My grandparents… Sandy Ragsdale Sandy Ragsdale May 2018 I am a survivor of ovarian cancer. I am also a survivor of Crohn's disease, having…

Sandy Ragsdale Sandy Ragsdale May 2018 I am a survivor of ovarian cancer. I am also a survivor of Crohn's disease, having… Sayla Hachey Sayla Hachey April 2018 Ovarian cancer has taken a lot from me. Most painfully at this point is that it…

Sayla Hachey Sayla Hachey April 2018 Ovarian cancer has taken a lot from me. Most painfully at this point is that it… Merry Vediner Merry Vediner March 2018 My story began in early summer of 2014. I was visiting with a friend who had…

Merry Vediner Merry Vediner March 2018 My story began in early summer of 2014. I was visiting with a friend who had… Teri Giangreco Teri Giangreco February 2018 For the first ten months of 2016 I was the healthiest I had ever been. I…

Teri Giangreco Teri Giangreco February 2018 For the first ten months of 2016 I was the healthiest I had ever been. I… Carrie Gordon Carrie Gordon January 2018 In 2006, I hadn't felt well and knew I had a colonoscopy coming up. Then, during…

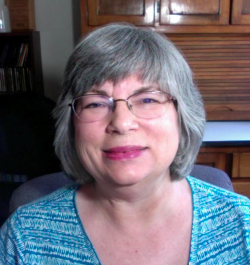

Carrie Gordon Carrie Gordon January 2018 In 2006, I hadn't felt well and knew I had a colonoscopy coming up. Then, during… Diane Sarver Diane Sarver December 2017 My name is Diane Sarver and I am 67 years old. I am a mom, a…

Diane Sarver Diane Sarver December 2017 My name is Diane Sarver and I am 67 years old. I am a mom, a… Kelly Shafer Kelly Shafer November 2017 It was April 2016. I was 56 and life was good. My husband of 18 years…

Kelly Shafer Kelly Shafer November 2017 It was April 2016. I was 56 and life was good. My husband of 18 years… Virginia Geter Virginia Geter October 2017 Homeless by accident I was moving out of my apartment because I wanted to relocate somewhere…

Virginia Geter Virginia Geter October 2017 Homeless by accident I was moving out of my apartment because I wanted to relocate somewhere… Poupak Sebti Poupak Sebti August 2017 Good friends have said, "But you must have seen it coming."1 The truth is that I saw…

Poupak Sebti Poupak Sebti August 2017 Good friends have said, "But you must have seen it coming."1 The truth is that I saw… Amanda M. Por Amanda M. Por July 2017 I was 25. I had just moved to a new city, started a new job,…

Amanda M. Por Amanda M. Por July 2017 I was 25. I had just moved to a new city, started a new job,… Jana Freiberger Jana Freiberger June 2017 I am 59 years old and live in Longview, WA with my husband of 33 years,…

Jana Freiberger Jana Freiberger June 2017 I am 59 years old and live in Longview, WA with my husband of 33 years,… Barbara Keepes Barbara Keepes April 2017 On Memorial Day weekend of 2011, I brought home a new miniature schnauzer puppy, Sherman. For…

Barbara Keepes Barbara Keepes April 2017 On Memorial Day weekend of 2011, I brought home a new miniature schnauzer puppy, Sherman. For… Kay Dee Cole Kay Dee Cole March 2017 My cancer journey started like so many others. It was a complete surprise. My life…

Kay Dee Cole Kay Dee Cole March 2017 My cancer journey started like so many others. It was a complete surprise. My life… Donna Gilmont Donna Gilmont February 2017 For close to 35 years, (from 1977-2011), my husband and I lived in three Third World…

Donna Gilmont Donna Gilmont February 2017 For close to 35 years, (from 1977-2011), my husband and I lived in three Third World… Cindy Plummer Cindy Plummer January 2017 In the summer of 2015, at the age of 58, I made a doctor's appointment to…

Cindy Plummer Cindy Plummer January 2017 In the summer of 2015, at the age of 58, I made a doctor's appointment to… Anna DeMers Anna DeMers November 2016 I am a Type A personality. I have a lot of energy and will power through…

Anna DeMers Anna DeMers November 2016 I am a Type A personality. I have a lot of energy and will power through… Jane Ridley Jane Ridley October 2016 It was an unusually warm and sunny day in May of 2013, I was driving --…

Jane Ridley Jane Ridley October 2016 It was an unusually warm and sunny day in May of 2013, I was driving --… Julie Lund Julie Lund August 2016 On August 2, 1989, my life changed when my doctor stood by my hospital bed and…

Julie Lund Julie Lund August 2016 On August 2, 1989, my life changed when my doctor stood by my hospital bed and… Laurel Pollock Laurel Pollock July 2016 When I first noticed a problem, it was around Christmas of 2013. I had a stomachache…

Laurel Pollock Laurel Pollock July 2016 When I first noticed a problem, it was around Christmas of 2013. I had a stomachache… Jana Freiberger Jana Freiberger May 2016 In May of 2015 I noticed a recurrent feeling of unease in my lower abdomen. I…

Jana Freiberger Jana Freiberger May 2016 In May of 2015 I noticed a recurrent feeling of unease in my lower abdomen. I… Marnel Groebner Marnel Groebner April 2016 In 2010, at the age of 50, I retired. I was active, ate healthy and was…

Marnel Groebner Marnel Groebner April 2016 In 2010, at the age of 50, I retired. I was active, ate healthy and was… Kathleen Fallon Kathleen Fallon March 2016 This is a story that has no ending. It is a story that has evolved over…

Kathleen Fallon Kathleen Fallon March 2016 This is a story that has no ending. It is a story that has evolved over… Melissa Hopkins Melissa Hopkins February 2016 For a period of three years from 2008 to 2011, I experienced a whole year without…

Melissa Hopkins Melissa Hopkins February 2016 For a period of three years from 2008 to 2011, I experienced a whole year without… Mary B. Mary B. January 2016 I had some big decisions to make in July 2014. Like many who have been diagnosed…

Mary B. Mary B. January 2016 I had some big decisions to make in July 2014. Like many who have been diagnosed… Nancy Ferrell Nancy Ferrell December 2015 I was originally diagnosed with ovarian cancer on February 27th of 1995. I was 49 years…

Nancy Ferrell Nancy Ferrell December 2015 I was originally diagnosed with ovarian cancer on February 27th of 1995. I was 49 years… Tami Ward Tami Ward November 2015 My cancer journey began in January 2013 when I was awakened in the middle of the…

Tami Ward Tami Ward November 2015 My cancer journey began in January 2013 when I was awakened in the middle of the… Roselle Soriano Roselle Soriano October 2015 As I recently held our one and a half year old granddaughter, I was reminded that…

Roselle Soriano Roselle Soriano October 2015 As I recently held our one and a half year old granddaughter, I was reminded that… Susan Gianotti Susan Gianotti August 2015 My cancer journey began in September of 2013 when I was diagnosed with Stage III-B mucinous…

Susan Gianotti Susan Gianotti August 2015 My cancer journey began in September of 2013 when I was diagnosed with Stage III-B mucinous… Becki McCall Becki McCall July 2015 A year and a half ago was an exciting time for me because I was going…

Becki McCall Becki McCall July 2015 A year and a half ago was an exciting time for me because I was going… Monica Marvin Monica Marvin June 2015 In March 2013, I was living an ideal life. At age 66, I had a rewarding…

Monica Marvin Monica Marvin June 2015 In March 2013, I was living an ideal life. At age 66, I had a rewarding… Natalie Leithem Natalie Leithem May 2015 I am 53 and have been married to my high school sweetheart for almost 30 years.…

Natalie Leithem Natalie Leithem May 2015 I am 53 and have been married to my high school sweetheart for almost 30 years.… Sandra Morgen Sandra Morgen April 2015 NOTE: this month's feature focuses on a survivor's recent experience as an ovarian cancer advocate in…

Sandra Morgen Sandra Morgen April 2015 NOTE: this month's feature focuses on a survivor's recent experience as an ovarian cancer advocate in… Judy Teufel Judy Teufel March 2015 I have just celebrated 17 years since my diagnosis of stage III-3 ovarian cancer and surgery…

Judy Teufel Judy Teufel March 2015 I have just celebrated 17 years since my diagnosis of stage III-3 ovarian cancer and surgery… Sherry Hanson Sherry Hanson February 2015 In May 2009, while visiting family in Portland, Oregon, I underwent abdominal surgery, was diagnosed with…

Sherry Hanson Sherry Hanson February 2015 In May 2009, while visiting family in Portland, Oregon, I underwent abdominal surgery, was diagnosed with… Mary Evans Mary Evans January 2015 My journey began in November 2002 with four words, "You have ovarian cancer." My life was…

Mary Evans Mary Evans January 2015 My journey began in November 2002 with four words, "You have ovarian cancer." My life was… Peg Gauthier Peg Gauthier December 2014 I've been a runner for over 40 years. I started participating in marathons in 1983 and…

Peg Gauthier Peg Gauthier December 2014 I've been a runner for over 40 years. I started participating in marathons in 1983 and… Katherine Schneider Katherine Schneider November 2014 Despite being a nurse in great health, and current with my medical physical exams, on April…

Katherine Schneider Katherine Schneider November 2014 Despite being a nurse in great health, and current with my medical physical exams, on April… Elaine Dickson, with Daughter Laura Bernards Elaine Dickson, with Daughter Laura Bernards October 2014 Readers of "In Her Own Words" understand that every woman's experience with…

Elaine Dickson, with Daughter Laura Bernards Elaine Dickson, with Daughter Laura Bernards October 2014 Readers of "In Her Own Words" understand that every woman's experience with… Teena Jones Teena Jones August 2014 I am a four-time survivor of ovarian cancer over the course of the last eight years.…

Teena Jones Teena Jones August 2014 I am a four-time survivor of ovarian cancer over the course of the last eight years.… Nicole Miller Nicole Miller July 2014 In 2010, I was a 17 year old senior in high school – and my focus…

Nicole Miller Nicole Miller July 2014 In 2010, I was a 17 year old senior in high school – and my focus… Judy Fornia Judy Fornia June 2014 I am a retired RN with more than 25 years experience in health care management and…

Judy Fornia Judy Fornia June 2014 I am a retired RN with more than 25 years experience in health care management and… Phyllis Lang Phyllis Lang May 2014 I am 62 years old and married with two daughters (one who is 39 and one…

Phyllis Lang Phyllis Lang May 2014 I am 62 years old and married with two daughters (one who is 39 and one… Anita Krivitzky Anita Krivitzky April 2014 In the spring of 2010, as I was turning 60, I was working full time in…

Anita Krivitzky Anita Krivitzky April 2014 In the spring of 2010, as I was turning 60, I was working full time in… Martha Richards Martha Richards March 2014 I was diagnosed on St. Patrick's Day of 2006. In those days I was always rushing…

Martha Richards Martha Richards March 2014 I was diagnosed on St. Patrick's Day of 2006. In those days I was always rushing… Angel Gnau Angel Gnau February 2014 I am a four-time ovarian cancer survivor. My journey with ovarian cancer began in March of…

Angel Gnau Angel Gnau February 2014 I am a four-time ovarian cancer survivor. My journey with ovarian cancer began in March of… Diane R. O’Connor Diane R. O'Connor January 2014 September 11, 2001 dawned while we were in the Strawberry Wilderness in Eastern Oregon. Of…

Diane R. O’Connor Diane R. O'Connor January 2014 September 11, 2001 dawned while we were in the Strawberry Wilderness in Eastern Oregon. Of… Becky Coulson Becky Coulson December 2013 In May 2007, at age 63, I saw my doctor for a routine physical (including a…

Becky Coulson Becky Coulson December 2013 In May 2007, at age 63, I saw my doctor for a routine physical (including a… Miriam Hoelter Miriam Hoelter November 2013 I was 54 and my life was going along smoothly – busy as a school counselor,…

Miriam Hoelter Miriam Hoelter November 2013 I was 54 and my life was going along smoothly – busy as a school counselor,… Joanne Seeger Joanne Seeger October 2013 I was 58 years old in 1999 when I was first diagnosed with ovarian cancer. My…

Joanne Seeger Joanne Seeger October 2013 I was 58 years old in 1999 when I was first diagnosed with ovarian cancer. My… Marcy Westerling Marcy Westerling September 2013 At age 50, I was having a wonderful time and experiencing exciting work as a community…

Marcy Westerling Marcy Westerling September 2013 At age 50, I was having a wonderful time and experiencing exciting work as a community… Elaine Carter Elaine Carter August 2013 My ovarian cancer story started in 2004, when my longtime partner, Sara, was diagnosed with advanced…

Elaine Carter Elaine Carter August 2013 My ovarian cancer story started in 2004, when my longtime partner, Sara, was diagnosed with advanced… Angela Bonnington Angela Bonnington July 2013 I was 31 years old when I was diagnosed with stage III ovarian cancer in November…

Angela Bonnington Angela Bonnington July 2013 I was 31 years old when I was diagnosed with stage III ovarian cancer in November… Karla Theer Karla Theer June 2013 My mom was only 22 when her own mom died; at the time, I was an…

Karla Theer Karla Theer June 2013 My mom was only 22 when her own mom died; at the time, I was an… Bonnie Stockman Bonnie Stockman May 2013 I have had a passion for oriental carpets and textiles for most of my adult life.…

Bonnie Stockman Bonnie Stockman May 2013 I have had a passion for oriental carpets and textiles for most of my adult life.… Michelle Kendrick Michelle Kendrick April 2013 Editor’s note: this is a departure from our normal featured story in that it is told…

Michelle Kendrick Michelle Kendrick April 2013 Editor’s note: this is a departure from our normal featured story in that it is told… Bev Lipsitz Bev Lipsitz March 2013 This story starts in 1986. I was thirty-five years old. I had started having painful bowel…

Bev Lipsitz Bev Lipsitz March 2013 This story starts in 1986. I was thirty-five years old. I had started having painful bowel… Marilyn Goodman Marilyn Goodman February 2013 From the time I could remember, I wanted nothing more in the world than to be…

Marilyn Goodman Marilyn Goodman February 2013 From the time I could remember, I wanted nothing more in the world than to be… Carol Riley Carol Riley January 2013 In the late spring of 2003, I started having what felt like menstrual cramps, but at…

Carol Riley Carol Riley January 2013 In the late spring of 2003, I started having what felt like menstrual cramps, but at… Marilyn Guldan Marilyn Guldan December 2012 In December of 2010, while on sabbatical from my job at Intel, I was watching Dr.…

Marilyn Guldan Marilyn Guldan December 2012 In December of 2010, while on sabbatical from my job at Intel, I was watching Dr.… Diane Elizondo Diane Elizondo November 2012 Before I was diagnosed myself, I had some knowledge of ovarian cancer, unlike many women. Two…

Diane Elizondo Diane Elizondo November 2012 Before I was diagnosed myself, I had some knowledge of ovarian cancer, unlike many women. Two…